05/24 By Dr. Matsakis

Eclipsophobia and Eclipsomania

Everyone has a story about the eclipse. I went to Cape Girardeau Missouri, by the Trail of Tears State Park [1], where archaeologist Rusty Weisman gave an eclipse talk [2]. He said some Native Americans believed eclipses to be the opening of portals between the solid sky [3] and the spirits above. During the eclipse of 1889 the Paiute spiritual leader Wovoka had a vision that led to the second Ghost Dance movement, which promised to restore Indian lands to their pre-contact conditions [4]. The ranger also gave us an eclipse viewer, which was a metal pizza pan with a pinhole to project the Sun against a wall or even your palm. A nice idea, though simple colanders work better – at the end of this blog I show another purpose for the gift.

Observing the eclipse in Boston

We learned about Winter Counts, the pictographic histories kept by western Sioux tribes, where a pictographic symbol was drawn recording the most important or memorable event of each year. For the eclipse of 1869 we find pictures of the Sun with its Corona (the atmospheric halo of the Sun that is only visible in eclipses) along with Mercury and Venus.

Lone Dog Winter Count, 1800-1870, with year of eclipse circled. Source: Americanindian.si.edu

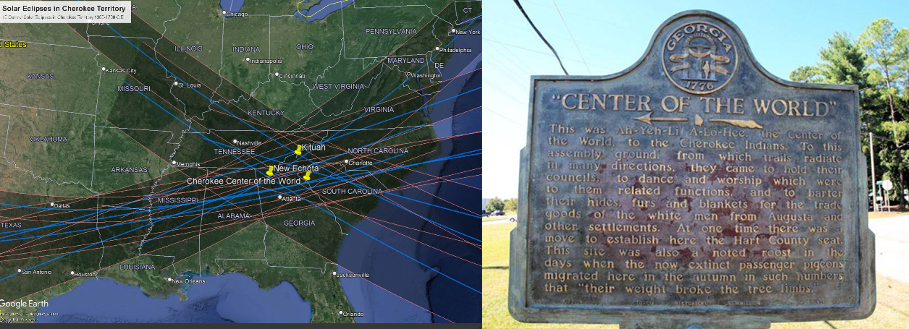

Interestingly, the computed eclipse tracks crossing Cherokee land over the centuries intersect very near the spot in Hartwell, Georgia that marked their center of the world.

Plot of eclipse paths over traditional Cherokee lands, courtesy Rusty Weisman. Source: ExploreGeorgia.org

Other cultures saw eclipses more ominously – often as a squirrel, frog, bear, wolf, or other evil entity trying to eat the Sun, and they’d make noises to scare it away [5]. Herodotus writes that in 585 BCE an eclipse stopped a battle between the Persians and the Lycians. Both sides interpreted it as sign of bad luck, and they made peace on the spot [6].

Not to be outdone on the doomsday end, some Christian preachers even predicted that the world would end with the eclipse of 1878. Sadly a Texas famer, Ephraim Miller, interpreted the eclipse that way too. Before taking his own life, he killed his young son with an axe to spare the boy from the apocalypse. Then, while his daughters were hiding under the bed, his wife went outside singing “Come on, sweet chariot”.

Of course scientists have a different take. We have always been interested in eclipses as something to study. Chinese records of an eclipse in 1815 BCE tell us that our slowing Earth has lost 14 hours in its rotation since this time, and Babylonian records show the Earth has lost 3.2 hours since 136 BCE [7]. The first successful prediction of a solar eclipse was by the Greek astronomer Thales, based on the Athenian astronomer Meton’s discovery that after 19.0002 years the Moon will again have whatever phase it has now (as in full or new moon). That’s called the Metonic cycle. The Babylonians earlier found a different cycle, called the Saros cycle. With this one the Sun, Moon, and Earth get into a straight-line relationship every 18 years and 11 days, which enabled them to predict some lunar eclipses. These two cycles explain why solar eclipses tend to come in pairs.

Maybe the first scientist to go beyond predicting eclipses was Aristotle. He noted the curved shadow of the Earth in a lunar eclipse and used that as one of his three proofs that the world was round [8].

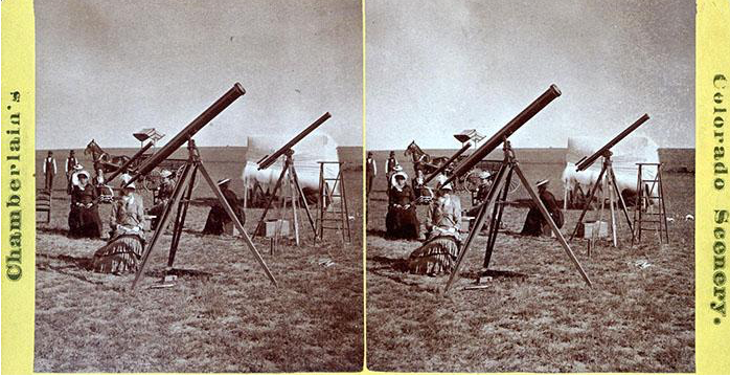

In the nineteenth century, scientists were interested in two main things. One was studying the Corona. Helium was discovered there in the eclipse of 1868, using a new instrument called the spectroscope. Ten years later, Thomas Edison received funding from a congressional grant managed by the Smithsonian to travel to Colorado to measure the brightness of the Corona with his new invention, a “micro-tasimeter” that he claimed was so sensitive it could measure the brightness of individual stars. It probably worked but the Corona was so bright it oversaturated the readout system. The tasimeter never became practical, despite his subsequent licensing of the idea to two companies for free [9].

Many other scientists were funded to observe that eclipse, but guess who wasn’t? Professor Maria Mitchell of Vassar. Director of the Vassar Observatory, Mitchell was famous for having discovered the eponymous comet. When she traveled to Denver with her team of female students to conduct their celestial research, Mitchell was even denied the railroad discount offered to male scientists. Undeterred, they paid their own way and carried out their work [10].

While Mitchell’s team produced great images of the Corona, they did not achieve the second goal of astronomers: to find Vulcan, a hypothetical planet orbiting closer to the Sun than Mercury. Scientists speculated Vulcan existed was because Mercury’s orbit deviated slightly but persistently from what Newton’s law of gravity predicted, given the effects of other planets. Specifically, Mercury’s position of closest approach to the Sun (the perihelion) rotated by a hundredth of a degree per century, as if this hypothetical planet was pulling Mercury’s orbit in that direction [11].

But somebody did report Vulcan’s discovery, and in no uncertain terms: Professor James Watson, observing from Wyoming. This brought him instant fame. Later Professor Lewis Swift, observing from Denver, also claimed to have found it. But their positions disagreed.

It turns out the reason the Vassar women didn’t find it is because there is no planet Vulcan [12]. Later, Einstein was able to explain Mercury’s motion with his General Theory of Relativity. His theory is that massive bodies warp the space-time around them, and what we call gravity is better explained as what happens when objects try to travel through that curved space in as straight a line as possible. Mercury is the closest planet to the Sun, with a highly elliptical (oval shaped) orbit over which its distance from the Sun changes by 20%. The warped space-time through which it travels results in the perihelion shifting, sort of like how a car without a steering wheel would move on a slanted racetrack. The numerical values that come out of the detailed calculations fit the data perfectly, or at least to within the uncertainty of the measurements [13].

Einstein also made a famous prediction involving eclipses. He theorized that starlight traveling near the Sun would be bent by the gravitational field of the Sun. Because the Sun is so bright, it would need to be blocked in order to properly observe this effect in action. And the Sun should also be in front of a star cluster, so you could see how much more the stars near the Sun got shifted compared to those slightly further away. Conveniently, in August of 1914 the Sun was slated to be eclipsed in front of the Hyades cluster, which is spread out over a distance about ten times larger than the Sun’s. Three groups were planning to observe it, but the onset of WWI precluded the effort. That war, termed “the Great Madness” by Bertrand Russell, proved fortunate for Einstein because it gave him a chance to find a mistake in his predictions [14]. When the war finally ended, Sir Thomas Eddington [15] organized a set of observations of the eclipse of May 29, 1919, and found exactly what Einstein predicted [16]!

So what was learned from the eclipse of April 8, 2024? The corona was imaged by many, and the science from that will take some time to process. Several people on the time-nuts listserve [17] reported that the frequency and phase of electrical power varied dramatically during the eclipse. That could have been caused by street lights turning on and solar power turning off. Maybe wind power too, because both winds and clouds dissipate during an eclipse. The ionosphere which is due to the Sun ionizing atoms in the upper atmosphere, showed wild fluctuations that also upset WWV reception [18]

My own efforts to do science were so-so. The sky looked white to me at low elevation, in all directions along the horizon. Others saw it as red. Could it have been sunlight scattered from outside the region of totality? Let’s see… the region of totality ended 85 km from where I was, and if we define the “height of the sky” to be the 10 km height of the cirrus clouds, we should have been getting some scattered light from the “sky” below 6.8 degrees elevation (the arctangent of 10 km/86 km). I can’t say if enough light would have been scattered to explain what I saw, especially as I may have simply seen street lights turning on [19].

Maybe more interesting are my observations of animal behavior. My bird-song app reported different birds singing before the eclipse than after [20]. Significant? Probably not. But I did observe some unusual behavior from my fellow primates. As totality approached, many started giggling. At the actual onset they began cheering and kissing. Fortunately, I was able to keep my head and do what had to be done. Here is a re-enactment of my successful effort to scare off the evil spirit:

And what was my reward for this noble deed? A five-hour traffic jam heading back to Masterclock’s headquarters in St. Charles.

Footnotes

[1] I had booked tickets to Austin six months before, but switched my reservations to St. Louis two days out because the weather reports for southern Missouri were so much better. That was the right move [1.5], yet I was shocked at how inaccurate the predictions of cloud cover were. The night before the eclipse it was predicted that at 2 PM Perryville would have 51% cloud cover and Cape Girardeau, 40 miles south, would have 35% cloud cover. Next morning the predictions for cloud cover had fallen to 23% and 19%. I saw no clouds in the sky then, and by noon the predictions had fallen to 1%.

[1.5] It was also the right move because of the history behind the Trail of Tears State Park. Every American should visit it, because our strength lies in not hiding the bad things in our past.

[2] The Cahokia Mounds Museum Society has posted a 57-minute presentation that Rusty Weisman made there a week before the eclipse found here

[3] Many cultures believed the sky was held up by pillars or that the Earth was suspended from the sky by ropes. Some Egyptian texts name mountains that provide the support. The Bible refers to pillars holding up heaven in Job 26:11. Pillars holding up the Earth are referred to in 1 Samuel 2:8, although Job 26:7 says “He hangeth the Earth upon nothing”. I am sure a good lawyer can explain these verses away. See BibleandScience.com

[4] By 1890 Sitting Bull, chief of the Lakota (Teton Sioux) Indians, who along with the (literally) visionary warrior Crazy Horse [4.5] tricked and defeated Custer at Little Big Horn, had given up fighting and even begun performing in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. This did not prevent reservation officers, also of the Lakota tribe, from shooting him in an altercation involving fears he would join this Ghost Dance movement.

[4.5] The partially completed and privately funded Crazy Horse Memorial is planned to be 563 feet high and 641 feet wide, which would make it the world’s largest mountain carving. This is generating a little controversy among native Americans, partly because of environmental issues and also because he was known for modesty, as well as for his generosity.

[5] Many royal deaths have been ascribed to eclipses, but this one is valid: in 1878 Mongut, the king of Siam, played by Yul Brenner in “The King and I”, died of malaria after travelling to an eclipse whose position and time he calculated himself. Obviously Hollywood did not do him justice. (See ScienceHistory.org.)

[6] Perhaps they didn’t all go blind because it is safe to look during totality, and only for a short time before and after totality is the uncovered part of the Sun not bright enough to force you to look away. Also, some soldiers may have had undiagnosed but permanent visual impairment. But don’t you try it! There were fourteen cases of confirmed eye damage from England’s eclipse of 1999, with varying degrees of severity. One of the “more serious” cases had looked at the Sun for 20 minutes without protection. See ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Less than 100 cases of observable retinal damage from the American eclipse of 2017 were reported (see npr.org), but you don't want to be one of them.

[7] We can accurately calculate the times of ancient eclipses from the orbits of the Moon and the center of the Earth. The spot where the Sun’s shadow hits the ground tells us how much the Earth had rotated.

[8] Another of Aristotle’s proofs was that as ships come to port the top of the mast was seen first and then more and more showed as the ship got closer. The third proof was that the North Star got lower as you went south, and other constellations became visible.

[9] Thomas Edison was a great inventor, and perhaps that is inseparable from the fact that he made several great mistakes. The invention of the phonograph, the movie camera, the fluoroscope, and the perfection of the incandescent light bulb far outshine his failures, many of which failed only because they were too far ahead of their time. Like talking movies and his tasimeter, which he brilliantly surmised could be used to detect unseen heavenly objects. We can forgive the “extreme optimism” with which he publicized progress on his planned inventions, but his treatment of Nikola Tesla was abominable. And he was worse than wrong when he argued against the alternating current (A.C.) we use today to bring electricity to our homes, though I have recently seen proposals to use D.C. instead of A.C. to reduce losses in long-distance transmissions.

[10] Aside from being paid less than men, not being allowed to use certain telescopes, and even being denied access to some astronomical meetings, she also had to contend with a widely quoted book by a prominent Boston doctor that claimed women should not go to college because too much use of a young woman’s brain would sap energy from other parts of her body, including her reproductive system. Mitchell’s performance at the eclipse did much to dispel such notions. After the eclipse she gave a very well-received public lecture in Denver, the proceeds of which went to the Colorado women’s suffrage movement. She also was an outspoken proponent of racial equality.

[11] There is precedent for an unknown planet perturbing the motion of known planets. Neptune was searched for and discovered because is gravity would explain why Uranus was not moving as Newton would have predicted.

[12] The hard part was being sure what looked like Vulcan was not a known star. This required precise measurements and accurate calibration. Later, both Watson and Lewis found second unknown planet-like objects in their data. But again their positions disagreed with each other. Attacked on all sides, Watson decided to dig a deep well at his own expense, in the hope that the telescope would block out enough of the Sun to reveal Vulcan in the daytime. Sadly, when a problem occurred in construction he rushed out without his jacket, caught peritonitis, and died at the age of 42. His replacement astronomer completed the project but found he could not observe stars, which is something Watson should have known because the scattered light from the sky around the Sun is too bright. Watson was quite a character, and also a shrewd businessman. He died rich enough to endow the James Watson medal, which is awarded every two years by the National Academy of Sciences for the best achievements in astronomy. Two of the last four recipients of this prize were women.

[13] See my blog “Good Things Take Time”. People are always trying to modify Einstein’s equations by adding a small term that doesn’t affect what we know about gravity but might reveal itself if we had better data. Some of these extra terms, if real, would imply that black holes are just very dense matter and not singularities impossible to escape from. To search for such extra terms a USNO astronomer, Al Fiala, combined data from his own eclipse observations with data from past eclipses to get accurate measurements of the size of the Sun. Needless to say, relativity withstood the test. But Al and his coauthors did find that the Sun was shrinking about 0.1% per century, a fact that could be ascribed to some unknown solar cycle.

[14] Einstein developed his theory in pieces, sometimes getting things wrong and realizing it later. Famously, he once proposed a term in his equations that would make matter repel itself at large distances. It is termed the Cosmological Constant, and he later called it his biggest mistake. However with the discovery of the accelerating expansion of the universe, that mistake has now become an insightful prediction.

[15] Eddington and Russell were both friends of Virginia Woolf. Last year I gave a talk on how their mutual discussions about relativity influenced her book “To the Lighthouse”. See also “Relativity, Quantum Physics, and Consciousness in Virginia Woolf's To the Lighthouse", by Paul Tolliver Brown, Journal of Modern Literature,Vol. 32, No. 3 (Spring, 2009), pp. 39-62.

[16] The Eddington experiment has many times been repeated and reconfirmed with better data. Using radio waves, the bending due Jupiter’s gravity was also observed. Not only that, but because Jupiter is moving it was possible to show that the “speed” of gravity is also the speed of light. Bent starlight is now a standard astronomical tool because a foreground galaxy (or even dark matter clump) can cause light from a distant galaxy or quasar to be focused or even split into several spread-out images to form what is called an Einstein Ring.

The remarkably dense JWST-ER1 galaxy and its Einstein ring, as captured by the James Webb Space Telescope last year.

(Image credit: P. van Dokkum et al., Nature Astronomy accepted, 2023)

[17] If you think time technology is cool, you may want to join the time-nuts listserve. Check out http://leapsecond.com/time-nuts.htm

[18] https://spaceweather.com

[19] Other people photographed pink or reddish light, and some photographs showed no low-elevation light at all. My iPhone’s pictures were poor quality, but did show some white cirrus clouds. This is one of several things I’ll pay more attention to if I go to Spain for the 2026 one. After all, progress is iterative.

[20] Before the eclipse my bird song identification app recognized a Northern Cardinal and a European Starling. During totality there were some birds singing, but not loudly enough for my app. Just after totality the app identified the Carolina Wren and Eastern Meadowlark. A little later the Northern Cardinal started up again.

About Dr. Demetrios Matsakis

Dr. Demetrios Matsakis attended MIT as an undergraduate and received his PhD in physics from UC Berkeley, where he studied under the inventor of the maser and laser; and built specialized ones in order to observe interstellar dust clouds where stars are born. His first job was at the U.S. Naval Observatory, building water vapor radiometers and doing interferometry to observe quasars and galaxies at the edge of the observable universe. After developing an interest in clocks, Dr. Matsakis would spend the next 25 years working hands on with most aspects of timekeeping – from clock construction, to running the USNO’s Time Service Department, to international policy. He has published over 150 papers and counting, but gets equal enjoyment out of beta-testing his personal ensemble of Masterclock products.

Dr. Demetrios Matsakis attended MIT as an undergraduate and received his PhD in physics from UC Berkeley, where he studied under the inventor of the maser and laser; and built specialized ones in order to observe interstellar dust clouds where stars are born. His first job was at the U.S. Naval Observatory, building water vapor radiometers and doing interferometry to observe quasars and galaxies at the edge of the observable universe. After developing an interest in clocks, Dr. Matsakis would spend the next 25 years working hands on with most aspects of timekeeping – from clock construction, to running the USNO’s Time Service Department, to international policy. He has published over 150 papers and counting, but gets equal enjoyment out of beta-testing his personal ensemble of Masterclock products.